The lepers in the Ghizou mountain village knew nothing of any Chinese Economic Miracle. Men without fingers or legs crawled in and out of the mine to feed their families. They used their stumps to scrape coal from a seam. If tunnels buried them no-one recorded their deaths.

Away from the mine corn flowered in contour banks built by Miao farmers. The owner of the leper’s scrapings sold the scrapings to the Miao. The Miao stretched the coal dust with clay and fed the mixture into their stoves. The stoves leaked warm smoke. It dried the corn of the short summer hanging in the rafters. They chewed the corn in the winter cold.

Zhaodong’s flats and smokestacks separated the road to Bangkok and Burma from the road to the Yellow River and Beijing on a Yunnanese plain between the mountains of the Miao.

Trucks, bicycles, and pony carts eddied in streams of sedans and minivans. A line of a dozen men shouted the virtues of a department store. Streets of shops with glass fronts dissolved in mazes of lanes. Asian pop blasted through a shop window. Children crunched on watermelon slices as they squatted on a sidewalk beside rambutan sellers.

The rambutam sellers held poles garlanded with hairy globes in weather-beaten hands. One balanced a bunch against weights in a handheld wooden frame. Another named the price.

In the lane beside them an old man helped an old woman stepping stiffly. Her legs ended in lumps wrapped in rags.

They passed a shop where men shouted, chopsticks clicked, and chicken bones thwacked on tiles. Rice wines, flavoured with fruit, coloured stands of carboys above the mounting chicken bones .

Where five roads embraced in a circle a shoeshine woman draped a towel across a chair on sidewalk. The letters on her towel spelt “Australia.” Her city had seen Australians for more than a century.

In 1894, Victorian doctor George Ernest Morrison said of Zhaodong-:

“On Sunday, April 1st, we reached the city…a walled Fu city with 40,000 inhabitants…The Mohammedans are still numerous in Chaotong…I had entered upon a district that had been devastated by recurring seasons of plague and famine. Last year more than 5000 people are believed to have died from starvation in the town and its immediate neighbourhood…More than anything else the district depends for its prosperity upon the opium crop…During last year it is estimated…that no less than three thousand children from this neighbourhood, chiefly female children and a few boys, were sold to dealers and carried like poultry in baskets to the capital…in time of famine children, to speak brutally, become a drug in the market. Female children were now offering at from three shillings and four pence to six shillings each.”

“Chinese Morrison’s” book, published in 1895, propelled him into employment with “The Times”, and the inner sanctum of the Chinese empire.

He was not the first Australian to gaze at the baskets in the markets of Zhaodong. He stayed at “the comfortable home of the Bible Christian Mission, where I was kindly received by the Rev. Frank Dymond,” where he met the Reverend Samuel Pollard, together with his wife, “and two lady assistants, one of whom is a countrywoman of my own.”

Buoyed by the success of Missionaries sent earlier, to the colonies of Victoria and South Australia, the Bible Christian Society opened its first Chinese Mission in Yunnan in 1885.Their imaginations fired by stories first heard in the Society’s Shebbear schoolrooms, Dymond and Pollard left their jobs and England in 1887 to found the Society’s second Chinese Mission in Yunnan. There they settled on Zhaodong, grew pigtails, learnt the language, and wore Chinese clothes.

Few Chinese converted to the west English faith. Red headed Pollard took to banging gongs and thumping an accordion to draw crowds in the streets. Five years after they arrived Dymond told Dr. Morrison he held high hopes of six enquirers.

Time had torn away the walls of Dr. Morrison’s city, and rice grew among potatoes in his poppy fields. Iron sheds masked markets where children offered to act as guides in exchange for the chance to practice speaking English and gave their mobile phone numbers to strangers.

Shenzen solicitor Mrs. S. and retired interpreter Ms. H. spent more time checking the quality of buckets and vegetables on the market stalls than they wasted time in bargaining about price. They and other friends had founded a charitable foundation in Hong Kong. They persuaded construction, corporate, and commercial lawyers to donate time and money to mainland poverty relief.

They were shopping to take a message into the mountains. The stove smoke leaked fluoride into the corn as it dried. The fluoride browned and rotted Miao teeth from inside out. The fluoride froze Miao joints. It killed men and women in their forties.

A driver squashed the women and their purchases into a hired minivan. The minivan wound through trucks and mule carts, market gardens, and mosques, inching between stallholders selling chickens and vegetables. It bounce on to a gravel road running into rolling hills. Coal belched black dust as they lumbered through the potholes towards the minivan. Potatoes flowered like roses in the fields.

The mountains glowered at the fields, their faces swathed in scarves of clouds. The minivan crawled into a ravine in a mountain’s skirt. A thin strip of concrete, set in mud, marked the way. It went up. And up. And up. The creek in the gully shrank to a silver wire.

Inside the clouds the world turned grey. Dusty men with exhausted faces stood beside a human rat hole. On one forehead a torch still shone. Coal dust smeared the ground beneath their feet. The Ghizou border passed unnoticed and unmarked.

Mud and rocks reunited the mountain and its ravine. The driver stopped. Men lugged luggage along a footpad through knee-deep slime. Ahead a minivan waited amid yellow flowering shrubs. It passed long, low, brown cottages emerging from mist. Men with wet hair held cues beside a billiard table open to the air.

As the light faded, the tops of the concrete road markers began to bounce instead of always rising, The minivan pulled aside from its narrow track. It stopped beneath an empty hilltop shrouded in grey fog.Mrs. S. and Ms. H. shrugged their shoulders into backpacks. They walked over the hill to an L-shaped building with a sign like a frozen fish separating its two stories. On broken asphalt men and boys played with a basketball most could not see.

Teachers and their families lived in two room units in the short concrete arm of the L. Thin heat blanketed a stove in a room with a broken window. Mrs S. and Ms. H. dropped their backpacks and checked the flue for leaks. Then they crossed a carpet of clover studded in wild strawberries as they slithered towards the school latrines. They had crossed the breadth of China from Shenzhen and Hong Kong to Zhaodong in three hours. It had taken six to climb the thirty vertical, twisting kilometres to Shimenkhan.

Morning brought light but not sun. Rain eased from murk. Mrs. S. and Ms. H. hung posters in the school yard. Driplets rolled down them.

Around the school stood and squatted hundreds of Miao. They rose in darkness on the fifth day of the Fifth Moon. They walked for many miles, to Shimenkhan, and the Festival of Flowering Mountain.

Women with bent backs and wrapped heads laughed with delight as they saw each other. Some wore embroidered white skirts and capes on top of their everyday black and blue. The little girls in the crowd admired and touched pink and orange scrunchies on their wrists and in their hair. Little boys ferreted space for playing marbles.

At the outskirts, buckwheat buns boiled in huge cauldrons, and stock bubbled in saucepans. Packets of coloured jelly spilled across the grass. Scrapers transformed cakes like huge cheeses into noodles. One cloth displayed the remains of a slaughtered pig. A policeman wandered through, nodding at people he knew.

Some brothers, fathers, cousins and uncles found soccer balls and walked down to a ground cut in the hillside. Others eased their jackets and caps nearer the beer truck hidden behind a rise.

Ms. H. beamed as the speakers passed the megaphone around. She slipped cups, toothbrushes, and toothpaste into their hands. People crowded in to see the cups from every angle. An hour passed before the crowd began to thin.

Once the crowd was thinning Mrs. S. and Ms. H. picked up their megaphone and packed up their prizes. A cassette player emitted scratchy music. The interpreter donned a white skirt and a cape embroidered red. Her smart boots led a team of techno-dancing girls. Another villager hunched over a movie camera on a tripod. The soccer players dispersed. Older women began singing folk songs, interspersed with hymns.

Basketball broke out behind the photographer. Men watched the flying ball between their visits to the hidden beer truck. Yellow dogs snuffled in clover. When the gloom came again, the soccer ground and the school yard emptied. A breeze skirled through a rug of trampled wrappers.

In the night the breeze dissolved the raining mist. The sun rose on blue waves of ranges. Three women like ants crawled up a slope. Baskets on their backs towered over their heads.A deep valley separated the school and the village centre. Near the school a boy herded cows around a bull tied to a stake. The bull pawed, kicked, and bellowed. The stake held firm.

After breakfast Mrs. S. and Ms. H. hiked along a trail like an army assault course. It drew them over and around mountains, and through mud, stones, corn, and potatoes, beyond the reach of roads, to the lepers who could not walk. Berries ripened like red and yellow olives on shrubs around them. The berries stood between soldiers and starvation when a Red Army’s Long March crawled across these ranges

“Hero’s food,” said Ms. H.

In the village of lepers, some stood, some squatted, some rolled out to see their visitors. No pupils played in the school, or in a woman’s blue and white eyes. Free medicine had killed the leprosy. It did not cure the injuries leprosy inflicted on subsistence farmers and their families. Nor did it halt the browning of their teeth, or the stiffening of their joints.

When Mrs. S. left the leper’s village, she left personal promises from law firms. She would find, send, and pay a teacher to live at the school. She would find prostheses for men to walk in crops instead crawling through mud to a mine.

Back in Shimenkhan, Ms Ho listened to people with rotten teeth. They shared a nation, but no language. As the interpreter spoke, Ms. H. wrote down the ideas of illiterate peasant farmers. Later she gave her notes to a construction solicitor in Hong Kong. He would see to it that their ideas were investigated and evaluated. Together they would see to it that his peers and colleagues funded implementation of the workable ideas.

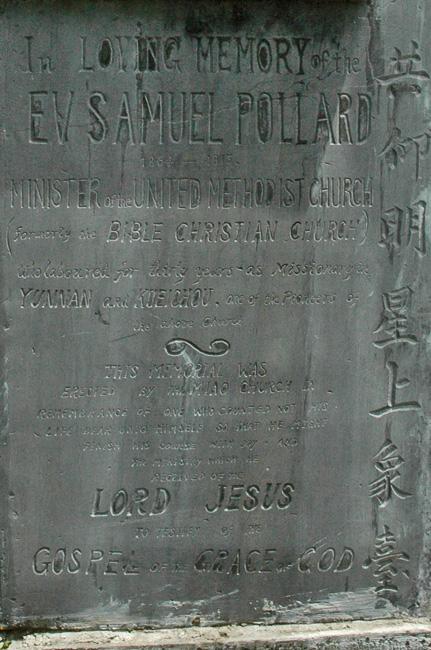

Mrs. S. and Ms. H. walked through the mud to a section of village set about a summit as the clouds gathered in again. They climbed a steep stair through ghosts of forests of the Flowering Mountain. Ferns and forget-me-nots tangled together in the fog at the head of a set of steps. Beyond the steps creepers cascaded from Reverend Samuel Pollard’s cross-topped grave.

Ten years after Pollard parted from Dr. Morrison, a small group of Miao from the mountains came to his door. He tried to preach to them. Few spoke any language but their own. Hundreds followed them. Pollard learnt their language, and traipsed through their mountains. Thousands listened- and converted.

A sympathetic landlord donated land for a Miao church in Shimenkhan. From his church Pollard drove devils of superstition and drunken debauchery out of the Festival of Flowering Mountain. The Miao told Pollard, “Our sons are our silver.” He responded “And your daughters are your gold.”

Ms. H. stepped closer the inscriptions around the letters spelling Pollard’s name.

“This is not the original grave…”

“The original grave was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. The Miao built it again.”

She peered at markings like runes.

“He invented the writing for their language.”

Then she looked at her watch, and led the way back down the steep steps, past the small church, and into the mud.

Sheets of small shrubs, with white flowers, fell away down the slope.

A small girl, part mountain goat, skipped in the gloom ahead.

Ms. H’s organization is a Christian organisation dependent on the continuing goodwill of local provincial officials, so it has not been named. It accepts donations and, in limited numbers, assistance from volunteers of any religious bent who are willing to work in health, education, and environmental poverty-relief projects in difficult conditions in remote regions in western China. It is also affiliated with private orphanages and desert reclamation projects.